Others before me have gone much farther into holy mysteries than I have done, but if my fire is not large it is yet real, and there may be those who can light their candle at its flame.

—A. W. Tozer

If I were to examine my life and discover what man has contributed more to my own spiritual growth, it would be no stretch to say that Aiden Wilson Tozer has enlarged my knowledge of God in great ways. No other Christian author has made me think and weep like Tozer has, and I believe I would not be writing this blog if not for him. In fact, I may not have been very much of a Christian presence anywhere if it were not for Tozer.

If I were to examine my life and discover what man has contributed more to my own spiritual growth, it would be no stretch to say that Aiden Wilson Tozer has enlarged my knowledge of God in great ways. No other Christian author has made me think and weep like Tozer has, and I believe I would not be writing this blog if not for him. In fact, I may not have been very much of a Christian presence anywhere if it were not for Tozer.

Most peers would cite C. S. Lewis as their favorite author, but while Lewis is most definitely a profound idea man, he has always paled against Tozer when it comes to describing and helping others discover the mystery of union with Christ. Tozer is as close as Evangelicals get to a genuine mystic, and that is a shame because, in its essence, knowing Christ is the very heart of the divinely mystical. Too few Christians today share that sort of grasping of the person of Christ that Tozer shows his readers, and I must believe that we would be far poorer in this understanding if not for Tozer.

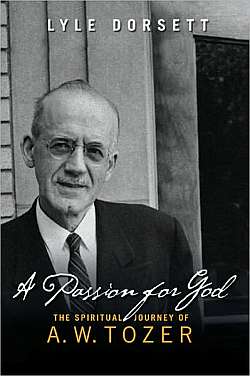

As much as I love Tozer the author, I knew little of the man himself. What a blessing that one of my favorite professors when I was student at Wheaton College, Dr. Lyle Dorsett of Beeson Divinity School (who also happens to be a renowned expert on C. S. Lewis), has written a biography of the patron saint of Cerulean Sanctum. Until this biography, I was not even aware that two previous works on Tozer’s life existed or else I would have devoured them eagerly. Despite knowing nothing of these previous bios, it was my great fortune to write Lyle a few years ago and hear from him that he was in the process of writing A Passion for God: The Spiritual Journey of A. W. Tozer. When the book made it to pre-order on Amazon, I put in my order right away.

A Passion for God is a difficult book, not something I expected on opening it.The primary difficulty comes from the fact that it contains a mere 150 pages of genuine biographical material, leaving a tad unquenched readers’ thirst to know more about the man who has been routinely labeled a genuine 20th century prophet. This is not to say that the scholarship here is inadequate, far from it, only that the private Tozer remains almost inhumanly private.

Dorsett chooses to open his examination of Tozer with the quote, “I’ve had a lonely life.” Indeed, as enormous a spiritual giant Tozer most definitely was, he proved a tough man to know. Even his family felt the distance, especially his wife Ada. Dorsett portrays a man who at once was close to Jesus and yet remote from the others who loved him. Once Tozer left the home of his youth, he eschewed visits, even going so far as to resist visiting his wife’s family, even though his mother-in-law was instrumental in introducing Tozer to the baptism of the Holy Spirit.

Tozer himself had been converted in 1915 shortly before his 18th birthday, praying to receive the Lord in the attic of his family’s Akron home. Having been born into a poor dirt farming household that later moved to the Rubber City, Tozer never forgot his humble roots. He took his disdain for wealth into his marriage to Ada in 1918; after his death it was revealed that he’d been giving half his paycheck back to the churches he had pastored, had refused a pension in the Christian & Missionary Alliance denomination in which he served for decades, and had taken no royalties on the paperback editions of his bestselling books.

Tozer pastored briefly in several poor churches in West Virginia and Ohio before ultimately receiving a call to Southside Alliance Church in Chicago where he stayed for most of his life. He didn’t like to drive, so his family stayed close to the church for years, even after the humble wooden church was replaced with a far grander building.

Dorsett ably recalls Tozer’s rise within the C&MA as the leaders of that group rapidly understood they had a winner on their hands. Or more like a blaze. For it seemed that wherever Tozer went, people caught fire. He went on to be a radio preacher on WMBI, the voice of Moody Bible Institute, and eventually garnered a nationwide audience.

In 1960, Tozer accepted a call to do nothing but preach at Avenue Road Church in Toronto, serving for three years before succumbing to a heart attack 45 years ago on May 12, 1963.

A Passion for God reveals much more of Tozer’s life than I just summarized. A few worthy notes:

- Both Tozer and his wife battled depression. Tozer once told his younger assistant pastor, Raymond McAfee, “If you want to be happy, never ask for the gift of discernment.”

- Tozer was a very staunch pro-American patriot and was deeply affected by World War II, maintaining a special admiration and care for soldiers and their families.

- Fearing that he’d succumb to too many human compliments, Tozer would avoid greeting his congregation at the door of the church after services, preferring to visit his church’s nursery and talk with young parents.

- Family devotion times at the Tozer household appear to have been just as difficult to schedule and pull off as they are in some of our homes.

- Students, especially at Wheaton College, Moody Bible Institute, and later at his church in Toronto, adored Tozer and his messages. Tozer returned that affection, maintaining a lifelong soft spot for young people.

- Tozer wrote one of his most famous works, The Pursuit of God, in one day while traveling by train to speak at another church.

- Despite not having much education beyond fourteen years, Tozer devoured as many books as he could read, electing to read widely on many topics, particularly writings of pre-Reformation Christians who had been largely ignored by Protestants of his time. Tozer himself never attended college or went to seminary. He routinely cautioned potential pastors about problems with the seminary system.

- Tozer spent hours in prayer and study in his office at the church, often prostrate on the floor. He even wore a specially tailored pair of pants that allowed him to pray longer while kneeling.

- For years, D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones tried (unsuccessfully) to get Tozer to come to London to preach at his church.

- Tozer defined workaholism, somehow managing to squeeze life enough for two people into one, yet when not traveling always made it home for the family dinner.

- Tozer later regretted some of the harsh statements he made about movies with Christian themes.

While A Passion for God is a deeply needed book on Tozer, I finished it only to have this wave of discontent wash over me. When the forwards, appendices, and index are removed, this book is a scant 150 pages. Because Dorsett revisits some issues repeatedly (Ada Tozer’s longing for a more intimate relationship with a man much more devoted to God than to his wife, for instance), each revisit adds little to what was already said, diluting the fullness of the material even more.

Sadly, the one truth I hoped would be revealed in this biography never seemed to gel for me: What made Tozer’s spiritual journey so profoundly different from all the other evangelical preachers of his time? Nor did I get a good feel for the one defining aspect of Tozer’s life that set him well apart from his contemporaries: his love for the mystic writers of Christianity. How and why did he latch onto them when they were largely ignored by others?

Dorsett also mentions that in later years Tozer received some critiques for being overly ecumenical, though he devotes only a page or so to this unusual fact about Tozer. This is definitely an underdeveloped thought considering Tozer railed against the increasing worldliness and liberalism he saw steeling away the heart and soul of Evangelicalism. In what may have been an overdevelopment, Dorsett devotes several pages to racial issues in Chicago toward the latter part of Tozer’s ministry there. In truth, Tozer did not have much to say on the issue other than he didn’t want to ignore reaching out to the black community of the time, nor did he like some of the contention, both from whites in his church and blacks in the surrounding neighborhood, that was forcing his congregation to relocate.

Leonard Ravenhill discussed his friendship with Tozer in a few teaching tapes I’ve heard of his, so I was surprised that nothing came of this in the book, especially since I know that Dorsett likes Ravenhill, too. Dorsett also noted that Tozer spoke at several Keswick conferences, though this is not developed at all. I would have liked to have known more about Tozer’s affiliations with some of the trends and schools of thought of the time.

Dorsett’s writing style is light and easy to read, though a tendency to move forward and backward in time makes the sections on Tozer’s childhood and early ministry more difficult to follow than they should be. And while I love Lyle’s passion for certain topics within Christianity, he makes his presence as author a bit too obvious on issues near and dear to his heart, something I loved about him when I had him as a professor but others may find intrusive.

A trade paperback, A Passion for God sports an attractive design, with an easy-on-the-eyes typeface and good whitespace. It includes a few pictures, too. For anyone interested in Tozer, it’s a worthy read, even if it does show that the patron saint of this blog had feet of clay. Then again, so does this blogger.