My Utmost for His Highest is one of the best-selling Christian books, if not the outright champ of devotionals. The book was first published in 1935, 18 years after its author’s death, and has never been out of print.

My Utmost for His Highest is one of the best-selling Christian books, if not the outright champ of devotionals. The book was first published in 1935, 18 years after its author’s death, and has never been out of print.

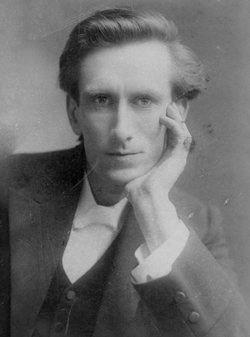

That author, Oswald Chambers, was coverted in part through the ministry of Charles Spurgeon and later went on to be a chaplain in the military. Chambers passed away in his early 40s from a ruptured appendix, and his wife was the one who compiled some of his writings into the devotional book we know today. The book was first published in 1935, 18 years after Chambers’s death, and has never been out of print.

I wanted to write about My Utmost for His Highest because I decided this summer to look through an old copy that has been sitting in our library for years. Aware of the reputation of the devotional, I thought it might be a good adjunct for me over the course of the next year. I have used A.W. Tozer’s Renewed Day by Day as devotional reading in the past and thought it helpful.

I am no expert on the history of Christian devotional works, so I don’t know if My Utmost for His Highest pioneered the layout of contemporary devotionals, but it adheres to the now typical form of a short Scripture passage followed by thoughts by the author, all arranged into 366 entries that fit on a page each.

To begin, I want to say that whatever Christian Oswald Chambers was, he was certainly a more noteworthy one than I am. For that reason, readers are invited to disagree with what follows, if for no other reason than as a testament to Chambers and the sheer number of this tome that have been sold, and in 39 languages.

But in reading My Utmost for His Highest (hereafter MUfHH), I wonder if the legacy of this devotional hasn’t set the stage for some of the problems we see in contemporary Christianity in the West.

1. While Bible text opens the daily entry, there’s often just a few words of it—followed by a lengthy exposition.

The one thing a casual glance at MUfHH reveals are a lot of ellipses. Scriptures are often cut down to their barest essentials. The June 30 entry is nothing more than “Agree with your adversary quickly… (Matthew 5:25).” Believe it or not, some Bible text for a day is even shorter than that.

My concern: Unpacking such a short passage out of context can lead to reading one’s agendas and presuppositions into the text (AKA eisegesis). Chambers does not equivocate on anything in MUfHH, so he has a forceful voice. This acts against people questioning his interpretation of the limited text and what should be done with it. This also sets up a tendency in readers to accept “little text with big explanation” as a norm for Bible exposition. But should it be?

One could argue that many devotionals follow this format, but I wonder if it doesn’t contribute to a wider problem of saying more about a text than the text supports. Of course, this can lead us into error, especially when the context has no similar exposition.

2. Keswick.

An unfamiliar term for many, Keswick is/was the location in England of a notable Christian Holiness conference and movement dedicated to the “higher life.” This movement is marked by the following beliefs:

- The baptism of the Holy Spirit (or “second work of grace”)

- Mystical union with God

- Holiness through Christian perfection

Some will recognize Wesleyan theology in these distinctives, but Keswick has been ecumenical in its reach. Nor was it an isolated theology, as many notable late 19th century Christians (including Andrew Murray, D.L. Moody, Hannah Whitall Smith, Hudson Taylor, and R.A. Torrey) were proponents.

Readers know I have written in support of the baptism of the Spirit and the positives (to a point) of Christian mysticism. However, it’s that third element of Keswickian theology…

My concern: MUfHH definitely shows the influence of Keswick on Oswald Chambers in that it is rife with Christian perfectionism. In fact, most of the entries contain some reference to the Christian working to perfect himself or herself to better experience God.

Some examples of how this manifests:

July 13: “My vision of God is dependent upon my character. My character determines whether or not truth can even be revealed to me.”

July 31: “Not only must our relationship to God be right, but our outward expression of that relationship must also be right. Ultimately, God will allow nothing to escape; every detail of our lives is under His scrutiny.”

August 2: “God does not give us an overcoming life—He gives us life as we overcome.”

August 9: “Are we living at such a level of human dependence upon Jesus Christ that His life is being exhibited moment by moment in us?”

August 24: “Don’t faint and give up, but find out the reason you have not received; increase the intensity of your search and examine the evidence. Is your relationship right with your spouse, your children, and your fellow students?…I am a child of God only by being born again, and as His child I am good only as I ‘walk in the light.'”

August 27: “The moment you forsake the matter of sanctification or neglect anything else on which God has given you His light, your spiritual life begins to disintegrate within you. Continually bring the truth out into your real life, working it out into every area, or else even the light that you possess will itself prove to be a curse.”

Does anyone else recognize how exhausting that perpetual self-examination is?

This kind of “I must strive to be perfect in order to receive anything from God” thinking extends from the idea that such perfection is possible this side of heaven. Sadly, it also counters the more biblical reality that Christ alone is the perfection of the born-again believer, and that Christ’s perfection is finished.

Even the title of the devotional itself offers a hidden conditional, that to get God’s highest requires one be perfect enough to deliver one’s utmost. MUfHH contains a LOT of this kind of idea, which leads to the next issue.

3. Talk of Grace, but followed by Law.

MUfHH talks much about God’s grace and how the believer can grow in it. In this, it reads like an instruction book on how to be a better Christian.

My concern: To talk of grace and immediately suggest something the believer must do to better his or her spiritual state isn’t the Gospel. Our sanctification is driven by God, not by relentless examination and working harder to be better Christians. Jesus alone is both the author and finisher of our faith (Hebrews 12:2). It is He alone we trust to finish the work He began in us (Philippians 1:6). If anything, our striving only gets in the way of genuine sanctification through God working His work in us.

MUfHH is loaded with striving. Almost every entry tells us what we’re not doing right and what we should do to fix it.

I offer the following little check of my own accord. You can take it for what it is worth. I believe it is in keeping with the Bible’s understanding of both Law and Gospel.

When I feel discouragement or despair in reading spiritual works, it is likely I am encountering the Law. The Bible makes it known repeatedly (and I will leave you to examine the many verses in support) that the Law illuminates every way in which I am deficient before God. How can one not feel despair in such a case?

But grace provides the opposite feelings: hope and joy. Christ overcame the curse of the Law. This is the heart of the Gospel.

Rather than being encouraged by much of MUfHH, my personal reaction has been discouragement in the form of “well, there’s just another spiritual discipline I’m not doing or not doing correctly.” Considering that nearly every entry in MUfHH consists of some way in which you and I are not being the best Christian we should be, it feels very Law-based, no matter how much grace is supposedly espoused. To begin an entry with talk of the grace of Christ but then to talk about how poorly I’m doing in apprehending it and what I should do to fix things, is not the best way to encourage Christian growth or the kind of freedom the Gospel delivers.

This is my greatest apprehension regarding this Christian classic. It’s not that it doesn’t encourage readers to go deeper in their faith in Christ, but it has a tendency to make a millstone out of this path to a deeper life in God.

To be entirely transparent, I’m unclear how most people can read My Utmost for His Highest and not despair at their inability to pull off the many solutions Chambers requires to counter the average Christian’s myriad failings. One day tells of what you are doing wrong, only to be followed by the next day telling something else you are doing wrong, and on and on. How this proves helpful to Christian growth is lost on me. What I come away with instead is a large burden that is my terribly practiced Christian life, which I appear to be performing atrociously despite God’s grace.

If anything, I see the striving that results at the heart of American Christianity. Do better. Work harder. Fix, fix, fix.

But where is the freedom of the Gospel in this? Where is the rest, in that a Christian can lay down all the striving, all the self-made righteousness and perpetual examination, and know that Jesus said on our behalfs, “It is finished”?

*****

I’m always willing to consider that perhaps I’m not reading My Utmost for His Highest correctly. Still, I cannot escape that it feels like just another set of Christian rules and suggestions that I will inevitably fail to do perfectly. Beginning each day that way—well, I’m not sure how encouraging that is.

If you have differing thoughts, please comment below.