{Somewhere in this rant is a worthy post. My apologies to readers in advance that the worthy post didn’t materialize.}

In the course of reading a smattering of Christian blogs wrestling with the economic devastation laying waste to America, I happened across Al Mohler’s take on the subject. By the time I got done reading the last word, it was all I could do not to shake my head in disbelief.

To understand the rest of this post, please read Mohler’s post, “A Christian View of the Economic Crisis.”

Done? Okay…

The first thing that bothers me about Dr. Mohler’s post is that it appears to be caught in a classic, science fiction time warp. If I didn’t know better, I’d say Eisenhower was president.

This is a great problem for much of conservative Evangelicalism. We’re like Jefty in Harlan Ellison’s seminal short story “Jefty Is Five.” In that work, the narrator tells of a neighbor boy who remains five-years old all his life. Jefty’s radio plays dramas from the 40s and 50s that were canceled decades ago. Jefty sends away for secret agent decoder rings offered by cereal companies that no longer exist—and receives them in the mail. In short, Jefty never grows up, nor does the ethereal, dead, dusty world that swirls around him. And he scares the willies out of the normal people who encounter him.

When I read Dr. Mohler’s post, it’s like I’m perusing Jefty’s newspaper, and I can read how the corporations are leading our country to greatness, and every father receives a gold pocket watch (that matches his smoking jacket) after 40 years on the job because he worked hard and climbed the corporate ladder like all hard workers do, and, golly gee willikers, his company put out the best darned widgets at the best darned price, and if you ever had a problem with your widget, they’ll send a repairman in a pressed suit (and a tie, even!) who won’t charge you a dime, and he’ll have your problem solved in fifteen minutes or your money back plus 10 percent for your trouble.

And at night, angels tuck you into bed.

That’s how Jefty economics works.

Jefty economics bases its reality on the old advice that with a little hard work, and the right amount of pluck, any freckle-faced lad can himself embody the classic Horatio Alger story and become a captain of industry.

It sounds so swell.

This, however, is what the Bible says:

Again I saw that under the sun the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, nor bread to the wise, nor riches to the intelligent, nor favor to those with knowledge, but time and chance happen to them all.

—Ecclesiastes 9:11

Jefty economics can’t account for chance. It doesn’t allow that people may deviate from the climb to the boardroom by simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time.  It can’t account for the capricious whims of a college admission committee that this year (and this year only) thought that building ashrams in India was a more noble reason for selection than your solution to world hunger, therefore you had to settle for Podunk U. instead of Harvard. It can’t factor in that after you killed yourself for decades to crawl to a middle management position in Kludge Corporation of West Oconomowoc, the CEO’s mistress left him and, in a fit of pique, he sacked your entire department and farmed it out to bean counters in Pakistan. The next thing you know, you’re a greeter at Wal-Mart wondering how the American Dream passed you by.

It can’t account for the capricious whims of a college admission committee that this year (and this year only) thought that building ashrams in India was a more noble reason for selection than your solution to world hunger, therefore you had to settle for Podunk U. instead of Harvard. It can’t factor in that after you killed yourself for decades to crawl to a middle management position in Kludge Corporation of West Oconomowoc, the CEO’s mistress left him and, in a fit of pique, he sacked your entire department and farmed it out to bean counters in Pakistan. The next thing you know, you’re a greeter at Wal-Mart wondering how the American Dream passed you by.

Who can understand how these things happen? The Jeftys of the world would turn on their radios and give you the answer: “The Shadow knows….”

Welcome to the world of Jefty.

Only problem is, that’s not your reality or mine.

In some ways, I can’t fault Dr. Mohler. Seminary presidents, theologians, and academicians aren’t the best at taking the lifestyle pulse of janitors, taxi cab drivers, and third-shift workers at the old widget factory (who just lost their jobs because the Armani-wearing board of directors moved the work to Shanghai).

See, Jefty economics functions in such a way that the real world, with all its gritty, black ugliness, doesn’t exist. The Jefties of this world can’t see it. The people who are getting killed economically, and have been getting killed for a long time, never happen. They’re simply not there.

Here’s reality: The way we do business, the way we fuel our economy in this country, the way we have been practicing capitalism in the good ol’ U. S. of A. has come home to roost.

I’ve been watching what has been happening to the middle class over the years. It’s not pretty. Hard-working people have been watching their real wealth evaporate. Families I know who were adamant that they were going to maintain the conservative Christian ideal and keep mom at home are not only having to have mom work but are seeing both wage earners’ incomes stagnate to the point that polygamy sounds like the only viable economic option.

And as for the mantra that hard work gets you ahead, it’s time to let that Jefty-ism die. Perhaps at one time it was true, but I know so many people who are killing themselves with hard work and are getting nowhere because they aren’t the right kind of person, didn’t go to the right Ivy League school, didn’t take the Skull & Bones pledge, don’t know the right Masonic handshake, don’t have the right skin color, don’t have the right religious beliefs, and on and on.

I met a person several years ago who shames most of us in hard work. I watched that person get brutalized time and again by the kind of wicked people who populate so much of today’s corporate world. That wonderful person kept a clean nose, gave 210 percent all the time, was the last to turn off the lights at night, and got nowhere. There was always some Maserati driver in a corner office who made sure this person never got out of the cubicle. That constant heel to the neck hurt that person incalculably.

Truth is, I know too many people like that one. They’ve been the canaries in this economy’s coalmine for years. And now the mine’s caved in and gas is seeping into the depths. Is that a striking match I hear?

Here’s the worst part: The kind of people that flame out in the economy aren’t welcome in a lot of conservative Evangelical churches, those gorgeous, multi-million dollar edifices full of Jeftys.

I know because I’ve been in a few Jefty churches. I sat in a men’s Bible study at a prominent Baptist church as a half dozen captains of industry talked about “those people.” Just the other day, a friend told me that the pastor of his old church spotted him in a restaurant and just had to regale him with how wonderfully the new building plan was going and all the millions that he’d raised. Dropped all the monetary figures just to show my friend how stupid he was to leave such a dynamic church. But my friend knew this same church split earlier because a handful of its people had the nerve to evangelize poor Hispanics. You know, dishwashers, gardeners, and garbagemen. Those people. The ones you let into your corner office to dump out your trash can, but God forbid they should aspire to anything higher. Besides, they could never get into the country club—except perhaps as the catering help.

When I hear Dr. Mohler talking the way he does in his piece, I have to wonder if he knows how the sub-economy populated by the least of these lives. If he understands that we really are Two Americas and are becoming more so every day. When he says that people today invest in the same companies that Warren Buffett does, I’ve got ask: “Dr. Mohler, have you priced some of Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway stock lately? You might be able to buy some at $135,000 a share, but I sure can’t. And have you noticed that the Gateses and Waltons of the world who can plunk down $100,000 without batting an eye get offered a whole new world of higher-paying investments that Joe Sixpack can only dream about?” Then I’d like to introduce the seminary president to hard workers like Edwin Howard Armstrong. And then I’d introduce him to people who don’t have Wikipedia entries, people who broke their backs working and lost their homes anyway. People who don’t have Ivy League networks. You know, people to whom chance just so happened to happen.

Part of me says I’m being unfair, but part of me says I’m not.

Here’s the saddest part of all. The people who are still operating under the economic pretensions of the “I Like Ike” era are the ones who were looking the other way while the morally-challenged, who laughed all the way to the bank at the expense of the rest of us, engineered this fine economy we have now.

Yes, I’m angry.

I’ve been saying for years that the global economic game we’ve been playing is not even zero sum but negative sum. When the Church sat back and welcomed the Industrial Revolution like it was the Second Coming of our Lord Himself, we erected an idol that would eventually taint every part of our lives. I find it ironic to the nth degree that so many conservative Evangelicals are fighting the culture war tooth and nail, failing at the same time to see that the war itself is the natural outcome of what they welcomed 150+ years ago.

Christians cannot turn blind eyes to social and economic justice and NOT reap the whirlwind.

We conservative Christians gave up on reforming business practices. Left that to the liberals. No, a few of us tasted the wealth for a while and it intoxicated us. (“Hey, no fair, Dan! We compensated by starting a workplace Bible study to show we still cared about the souls in our companies. That counts, doesn’t it?”)

Despite what Mohler says, too much of how we lived was based on greed and short-term thinking. As long as our companies posted better figures quarter over quarter, who cared what havoc our practices would wreak down the road? Leave that for some other generation!

Well, that generation is here. And, too bad, we’re it.

Thanks, Jefty.

Though I normally don’t comment on the deaths of well-known people, I need to write about the loss of Jerry Falwell.

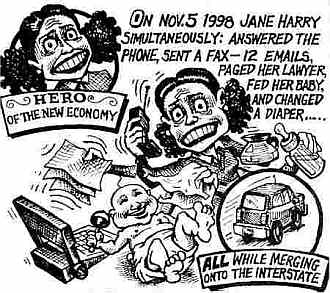

Though I normally don’t comment on the deaths of well-known people, I need to write about the loss of Jerry Falwell. People are going to bed at 4 AM and getting up at 7 AM. Homeschoolers are scheduled to the max trying to pack requirements in every day. Life has become a clumsy dance of “do this, then do that” and our days have come to resemble little more than a succession of nags.

People are going to bed at 4 AM and getting up at 7 AM. Homeschoolers are scheduled to the max trying to pack requirements in every day. Life has become a clumsy dance of “do this, then do that” and our days have come to resemble little more than a succession of nags.