I’ve been using the Internet since it was the old DARPANET, having sent my first email in fall 1981. Though I obviously use the medium, I am not a fan.

I’ve been using the Internet since it was the old DARPANET, having sent my first email in fall 1981. Though I obviously use the medium, I am not a fan.

Over the years, I’ve seen the conversation on the Internet turn more shrill and caustic. It especially bothers me when Christians add to the acid. Something about the Internet can bring out the worst in us, particularly when it comes to things interpersonal.

A couple weeks ago, I had lunch with Rick Ianniello, a fellow Christian and Cincinnati-area blogger, and we started to touch on the phenomenon of being angry on the Internet. In keeping with the gist of that talk, I’ve ruminated on that face-to-face conversation and want to share a few thoughts.

In fact, I’m going to jump right in and post my basic points:

People still desire interaction with others.

The inflammatory draws us because it provides points for interaction.

In a world of wrong, something in us needs to be seen as being a defender of what is right.

“An eye for an eye” is embedded in our sense of rightness.

Because Internet communication is so instant, its fleeting nature demands we respond instantly or else face exclusion from interaction.

People still desire interaction with others.

And thus completes the cycle.

I believe that this cycle explains much about our conversation through social media on the Internet and the way we interact with others through this faceless medium.

Thoughts:

Without a doubt, I spend far less time in face-to-face conversation with others. The excuse I hear is that people are so busy. I find it odd, though, that the vacuum that is the average day is increasingly filled with electronic communication, often hours of it. When someone posts an unusual (and often inflammatory) bit of info on the Internet, time was spent finding and reading that info. Add enough of that together and hours go by.

In a way, we suffer from a collective forgetful delusion: We no longer recall how we spent our time before the digital came to rule us. How did we interact before Facebook? How did we communicate before texting? How did we accumulate knowledge before Google? Instead of what we once did, which seemed to make us happy, we have substituted something else, and few of us are asking if we’ve made the right trade.

I used to spend a great deal of time talking with friends over a good meal. Now that almost never occurs.

But we humans still crave connectedness with others, so we post on Facebook or comment on blogs. It used to be long emails, but email is passé and Twitter taught us to condense everything into 140 characters. So we do.

And the way to generate conversation on the Internet is to post links to weird, interesting, or inflammatory statements we, or those who inform our worldview, make. Like the matador waving a red cape, we want the bull to notice us—except in this case, the bull is another person from whom we seek interaction.

We’re suckers for the red cape, aren’t we? It’s something in us. Both in waving it and reacting to it we reaffirm that we have significance at a time when so much of life seems pointless, redundant, and stupid.

“See? The bull charged. I still matter.”

We all want to matter. In the United States especially, inconsequence is a mortal sin. There’s always a cause to defend, an opinion to be had. Our democracy is built on the ideas of people who could not sit idly by without letting their thoughts be known. Something always has to be said. The Internet brings that ability to say anything about everything like no other medium in history. It is the public square on a globe-spanning level. Under that magnifying glass, every statement becomes inflammatory to someone.

So we react with what we’ve been taught from the Old Testament school of justice: an eye for an eye. If someone hits me verbally, I hit them back. I take their accusation and reverse it so that it hits them. Their strike is my counterstrike.

That sense of conversational revenge drives what passes for discourse nowadays. Few people ask whether it makes sense to lunge at the matador’s flung cape. They react with an animal’s mind and charge. That spear in their back demands a horn to the gut. And we witness all the gore played out in a public space.

Like a genuine bullfight, our reflexes must be lightning fast or else we get left out of the action. Who hasn’t come to an interesting Facebook post a couple hours afterward and found 25 comments and an already burned-out conversation? The matador and picadores went home. The flowers are already wilting in the ring. Too late.

The Internet waits for no man.

Impatience is the worst failing to pair with the inflammatory, and it’s here that we see the genesis of the anger that has come to dominate the Internet conversation and spill over into all other forms of discourse.

Before newspapers started to die because they are not fast enough to keep up with the lightning pace of information today, there was the letter to the editor. The op-ed section of the paper was our public arena for anger.

But the funny thing about a letter in those days was that it took time to write and mail. Plus, the conversation lagged by a few days. The inflammatory story of Tuesday became the slightly peeved letter to the editor of Friday. In the meantime, everyone had taken a few deep breaths and calmed down.

Whenever I was angry enough to write a seething letter, it’s funny how the seethe eased out of me as I wrote by hand. And more often than not, when I was truly livid, Jesus often said to me, “Why don’t you sit on this one for a day?” And I would. Ironic how many of those letters never got mailed. Something about a day passing made the anger of the moment seem like nothing more than an ill-thought, knee-jerk reaction.

Today, our online conversation demands the ill-thought, knee-jerk reaction. In fact, without that automatic, instant response, the Internet loses its raison d’être and no longer becomes the necessary touchpoint we have made it.

That said, for a lot of people, the Internet and social media are the only touchpoint with others they still possess. Yet what a sad trade this has been, as something precious has been lost in our rush to life online and too much coarseness has been gained.

People seem unhinged nowadays. Too many of us think we alone are the arbiters of all truth. Just witness the craziness in the aftermath of the death of Osama bin Laden, when people demanded to see his death pictures so they would believe. We’ve reached a point where only my seeing and my opinion define truth.

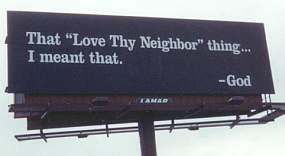

Christians need to take this all back and react differently. This is what we say we believe:

I am dust, a vapor that passes through today and is gone tomorrow.

All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God, even me.

I am to esteem my neighbor better than myself.

I am to love my enemies and pray for those who hate me.

All the law and the prophets are summed up in loving God and loving my neighbor, for love is the pinnacle.

Truth is truth apart from what I think or say; it can stand on its own and will go on without me.

The wise listen much and speak little.

“An eye for an eye” has been replaced by incomprehensible mercy, even in the face of hatred.

No one is unredeemable until he or she draws that final breath, so I must trust God in His dealings with people, particularly foes.

God has been patient with me and my slow growth, so I must be patient with others.

Jesus did not break the bruised reed or snuff the smoldering wick, and neither should I.

God made us to depend on each other because each of us is differently gifted by Him.

If you and I forsake gathering together in person, we lose something invaluable.

I can spend hours unpacking those realities for you, but you are smart people. You know how they should apply to our discourse and how we interact with others.

Now if we would only believe those truths enough to practice them, think how the world—even the online one—would be different.

It seems to be the human condition.

It seems to be the human condition.