The eyes are not here

There are no eyes here

In this valley of dying stars

In this hollow valley

This broken jaw of our lost kingdoms

In this last of meeting places

We grope together

And avoid speech

Gathered on this beach of the tumid river

Sightless, unless

The eyes reappear

As the perpetual star

Multifoliate rose Of death’s twilight kingdom

The hope only

Of empty men.

—Excerpted from T.S. Eliot’s “The Hollow Men”

They built seven houses on the former gas station lot. Yes, a violation of the physical laws of the universe, but I saw the houses with my own eyes.

Less than six months after my wife and I pledged our troth, I took a job with Apple Computer in the heart of Silicon Valley. Having lived my entire life in the Midwest, I expected some disorientation, but nothing prepared me for the future shock I experienced.

We settled in a two bedroom apartment in Sunnyvale—a name epitomizing idyll—nestled between AMD, Sun Microsystems, Yahoo!, and Lockheed Martin. As the local rubes, we wore our homespun naïveté on our sleeves, attempting to live as we had in the heart of the heartland. Our first agenda was to get to know our neighbors. Isn’t that how they do it back in Mayberry? Our complex was a chutney of Indian, Hong Kong, and German immigrants, all drawn to the computer capital of the world. We saw them through their windows, watched them walk into their apartments, but every knock on the door was met with a vast unanswered nothingness. We spent three-and-a-half years attempting to meet our neighbors. In the end, we met no one.

How to describe the eerie feeling when you knock on someone’s door, can hear people talking inside, but no one answers. Worse yet was to descend the staircase in the morning only to see the people below us attempting to leave, but instead scamper back inside like so many timid mice when the cat’s around.

Our Hong Kong ex-pat neighbors stayed invisible. The Indians would be out and about talking in English, only to change to Bengali when they noticed us coming. Conversations consisted of them looking confused when we said, “Hi, we’re the Edelens…,” before they distanced themselves from our outstretched hands.  The Germans, who inhabited the farthest buildings in our complex, would gather at the pool in their micro-bikinis and thongs and play a sort of game called “Let’s See How Long We Can Ignore the Two Americans Crashing Our Party Before They Go Back Where They Came From.” Never in my life had I introduced myself only to have someone laugh and turn back to his friends as if I were a kind of comedic, talking vapor.

The Germans, who inhabited the farthest buildings in our complex, would gather at the pool in their micro-bikinis and thongs and play a sort of game called “Let’s See How Long We Can Ignore the Two Americans Crashing Our Party Before They Go Back Where They Came From.” Never in my life had I introduced myself only to have someone laugh and turn back to his friends as if I were a kind of comedic, talking vapor.

Hundreds of people lived in that complex; surely someone would warm to us.

Only later did we learn from one of my immigrant co-workers that American television and movies piped into Hong Kong and India had effectively taught everyone in those countries that every last American carried a Smith & Wesson with a caliber big enough to down a 747. Open the door and you risked having Dirty Harry and his wife, Foxy Brown, put a slug in your head just for the fun of it.

We had a good church, but we noticed little spots of social leprosy there, too. When our official small group meeting was over, you would have thought someone had finished our prayer time by yelling, “Grenade!”—the room cleared that fast.

The excuse was always the same:

Me: “You’re going to work at 9:00 PM?”

Not Me: “Yeah, gotta fix some code for the video drivers.”

Me: “Wanna grab a coffee with us before you head in?”

Not Me: “Sounds great, but no time. Maybe next week.”

Next week rolls around. Lather, rinse, repeat. Evidently, not much got done; the video drivers, product manual, or marketing plan never received their promised healing. Nor did we ever share a coffee. Not once.

Our first church attempt had been far less successful. We were new to the area, but the church’s small groups were all closed. Weren’t accepting new people. One older couple did invite us over to their house, which oddly enough reminded me of something out of “Ozzie and Harriet,” and we enjoyed one of the three homecooked meals we had in our three-and-half years in the Valley. But the small groups were closed and most people rushed home after the Sunday service. Work? Seemed to always be the reason. No reason for the closed groups, though—at least that we could tell.

We had some friends who lived on the other side of San Jose whose new house had about ten feet of yard all the way around it. They wanted to paint the outside of their house a certain color, but the housing association that owned the land only approved five colors and their choice wasn’t one of the five. Nor did they have any say about their landscaping. Kiss the planned cherry tree goodbye! In fact, our friends didn’t technically own the outside of their home—just the inside. There wasn’t much to the outside anyway. You could pass the Grey Poupon through one kitchen window to the next. To step outside their patio door was to promptly step into their pool. The patio itself was more a concept than an actuality.

But the neighborhood was even more perplexing than the limitations, as houses that had been sold the week before never saw new occupants. In those mad, housing run-up days, the buyers flip-sold the house and pocketed upwards of $50,000 by doing so. The result was a neighborhood dotted with homes perpetually for sale, yet not even a year old—possibly forever empty.

All this time, the disquiet in my soul grew.

In the Valley, the measure of a man was his job, his affluence, his earning potential. I’d seen glimpses of this back in Ohio, but like a city-sized thumb it pressed down on you here with a new kind of ferocity. And affluence wasn’t just the measure of men. The teenager drove a Porsche Boxter. Private schools, each more tony than the next, sprouted in the hills, sponsored by aging rockers with kids (or grandkids), who had to ensure the little darlin’ got into Stanford with a full ride. This led to the quandary of choosing between battling school fundraisers, this one featuring Neil Young and that one headlining Joan Baez. (Tip: Go for Neil.) Because we all know that unless Junior gets into that accelerated pre-school, he’ll never take home the sheepskin from that Ivy of the West, dooming him to a future managing an ice cream shop with only twenty flavors.

Don’t ask any of those measured men to give, though. A study came out while we were there noting that residents of the Valley gave only 2% of their income to charity. A man would never consider dropping a measly 2% of his income into his 401k, but 2% was good enough for the least of these. Maybe the parents of those least people should have worked harder to finagle them into a name private school.

It was in our last weeks in California that they built the seven houses on the former gas station lot near the corner where we lived. Somehow they put a driveway down the middle of that, too. Einstein would have had all his wackiest theories proven by the way the architects had folded space to make room for seven houses. Seven houses that were nearly touching, but for all that closeness might just as well been on different planets. As we had learned, proximity did not mean neighborliness. A lot of other things were missing, too. The blur of life left everyone panting for something to make life worth living. But in the Valley, what was truly sacramental eluded many.

We slave away at jobs that have little meaning so we can buy things that provide no lasting meaning at all.

We willingly severed our connection to the soil from which God first fashioned our original ancestor because soil is dirty and doesn’t look good on our Steve Maddens.

We lost God in the blur of a million spurious activities that hold no eternal value.

We do not pray because our televisions and computers bury us under the problems of the entire world, so we don’t know where to begin. We don’t have the time anyway.

We love the material and tolerate people rather than the other way around.

Our savior died on a rough-hewn cross and rose again, yet many of us who claim His name find our iPods to be more real and the music gracing them more comforting.

We talk about community, but we cannot name our neighbors’ children, nor have they ever stepped foot in our home.

Time with the family is rated by quality, not quantity.

And the very things of God that He created for our benefit are forgotten amid the hustle—and cheapness—of modern life.

It’s disheartening. But it doesn’t have to be this way. We don’t have to lie down and accept this as the only way to live. Yet so many Christians, the ones who hold the breath of God in their spirits, are all too willing to join the world’s parade when confronted with the discordant times we live in. Need I remind us, the Church was not founded on “If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em!”

What’s needed are people who understand that the simple ways we abandoned in our rush to modernity have meaning because God Himself gave them meaning. Lose them and we lose part of the eternity He placed in our hearts.

To cow to the times and say that nothing can be done because we live in a fallen world is to fundamentally deny that He that is in us is greater than he that is in the world. This is not blind utopianism, but a call to live lives wholly consecrated to manifesting God’s will for us in a world tainted by sin. It’s a call to rediscover what is pleasing to the Lord in each small moment of the day, whether we be baking bread or sharing our childhood stories with the next generation. It’s dedicating every thought, every action to the Lord in a way that finds His sanctification working out through us in the tiny slices of this present day. It is the heart of worship.

In the days ahead, I’ll be exploring how we Christians can challenge the assumptions of Modernism and find what is truly of God in a discordant age too preoccupied with the earthquake and storm to hear God in the whisper.

Thanks for reading.

***

So much of what we do as a Church in this country is devoid of meaning. We’ve allowed the Enemy to strip out so many simple and sacred aspects of life that we didn’t notice they’d gone missing one by one until it was too late.

Other posts in the “Unshackling the American Church” series:

Every week I get private e-mails from folks saying that this blog has been a blessing just by being unafraid to confront the Gordian Knots that face the American Church. I thank every one of you who have written. Your notes mean the world to me.

Every week I get private e-mails from folks saying that this blog has been a blessing just by being unafraid to confront the Gordian Knots that face the American Church. I thank every one of you who have written. Your notes mean the world to me.

Strong’s Concordance lists that troubling word mammon as “avarice (deified).” A better definition one cannot possibly hope to unearth. Unearthing a Church buried under layer after layer of avarice deified, on the other hand, poses a challenge to us American Christians, so inured are we to the materialism that masquerades as legitimate culture in this country.

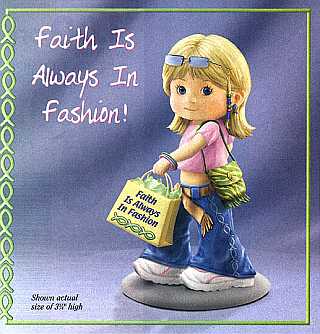

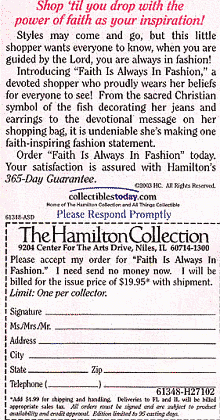

Strong’s Concordance lists that troubling word mammon as “avarice (deified).” A better definition one cannot possibly hope to unearth. Unearthing a Church buried under layer after layer of avarice deified, on the other hand, poses a challenge to us American Christians, so inured are we to the materialism that masquerades as legitimate culture in this country. What I cropped out of the picture is the sickening description for this figurine. You can find it at left. As a freelance commercial writer who’s a Christian, I’d rather be dragged over a pile of broken glass with an alcohol bath chaser than write what you see reproduced here.

What I cropped out of the picture is the sickening description for this figurine. You can find it at left. As a freelance commercial writer who’s a Christian, I’d rather be dragged over a pile of broken glass with an alcohol bath chaser than write what you see reproduced here. The Germans, who inhabited the farthest buildings in our complex, would gather at the pool in their micro-bikinis and thongs and play a sort of game called “Let’s See How Long We Can Ignore the Two Americans Crashing Our Party Before They Go Back Where They Came From.” Never in my life had I introduced myself only to have someone laugh and turn back to his friends as if I were a kind of comedic, talking vapor.

The Germans, who inhabited the farthest buildings in our complex, would gather at the pool in their micro-bikinis and thongs and play a sort of game called “Let’s See How Long We Can Ignore the Two Americans Crashing Our Party Before They Go Back Where They Came From.” Never in my life had I introduced myself only to have someone laugh and turn back to his friends as if I were a kind of comedic, talking vapor.