People were praying and studying the Scriptures before the Titanic rammed the iceberg.

Life was normal—and then disaster struck. Many good Christian people died that night, taken down to a watery grave in a ship designed with hubris and shortsightedness.

I say this because I want people to understand that God did not save every Christian aboard the ill-fated “unsinkable” ship. Jesus put it another way:

Or those eighteen on whom the tower in Siloam fell and killed them: do you think that they were worse offenders than all the others who lived in Jerusalem?

—Luke 13:4 ESV

What does all this have to do with business practices in the 21st century?

If we are not prepared, if we’ve no answers, we cannot count on escaping the natural outcome of the business trends of our times. Given how the Church in America is ignoring many damaging business practices, many will surely go down with the figurative ship when it finally strikes the iceberg.

We simply can’t ignore the problems anymore.

As we’ve seen in this series, the Industrial Revolution helped Social Darwinism gain traction and change the entire structure of the world economy. It also took parents out of their home to work in a remote factory/business, ultimately harming the family unit in the process by creating fracture lines that were never intended by God.

The Church’s response to these upheavals has been one of initial assent and reactions to problems after the fact instead of decisive actions ahead of the trends. This has led us to a day in which many Church and parachurch organizations simply mouth the status quo when it comes to work and employment issues that confront the average Christian employee.

Plenty of fingers point in thousands of directions by well-meaning Christians attempting to out the causes of the cultural death-throes we see around us. Yet the fact that our business practices may be a major component of the downward spiral is never questioned by Christians. Christian authors write Christian books about how to be Christian business leaders without ever questioning if the fundamental structure of business itself is hopelessly broken. Well-known pastors hold up Christian business leaders as examples, particularly to men, but never ask if the very system those leaders uphold is deviant at its core.

You can plate a 1975 AMC Pacer in 24k gold, but underneath all that gilding it’s still an ugly, undependable wreck of a car.

Folks, it’s not about the right to have a “Footprints in the Sand” poster in your cubicle. It’s not about being able to hold a lunch-break Bible study on company grounds. It’s not about adapting wisdom from Solomon to your job. All those are incidentals that ultimately will not make a shred of difference unless we get to the heart of today’s business practices and the Darwinian engine driving them.

The litany of corporate ills brought about by Darwinism is lengthy, but I’ll highlight nine for further comment:

1. Selfishness & greed

2. Expediency

3. Globalization & consolidation

4. Offshoring, outsourcing, and H-1B visas

5. Age-ism

6. Downsizing

7. The forced elimination of the Middle Class

8. Unnatural family situations that lead to stress and family breakdowns

9. Corrupt business practices adopted as models for the Church.

I noted in the second installment in this whole series (Economic Systems) that I believe that capitalism is the best economic system we’ve got—when it’s governed by a Christian worldview. That latter part is critical. But Christianity no longer informs business practices, Darwinism does. And at the heart of Darwinism is selfishness.

One of the most popular Darwinian tomes of the last fifty years is Richard Dawkins’s The Selfish Gene. The title alone says it all. Darwinism’s main goal is for an organism to pass along its genetic material at all cost. In a corporation this means that the corporate “genetic material” is more important anything. And that “anything” can include ethical behavior, loyalty to employees, and environmental responsibility.

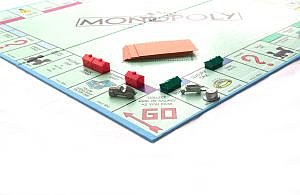

A study several years ago tracked the outcome of a structured game played with multiple players. There were two ways to win the game: an individual player could try to gain more chips than his two closest competitors combined (win-lose), or all players could cooperate toward a common goal that allowed each person playing to meet winning conditions (win-win).  In trial after trial, all the participants tried the win-lose scenario of cornering the market on chips. Because the win-lose scenario was easier to play but almost impossible to achieve, no one ever won the game. Even when individuals began noting this, they still played the win-lose scenario simply because the other players were. Now the win-win scenario required some foresight and thinking to achieve, but could be accomplished far more easily than the win-lose outcome. Yet time and again players refused to play the win-win game even though it was actually more challenging and fun to play. A clear winner and loser were necessary. Darwinism’s conceit is that it speaks to the natural, unredeemed man fluently, while Christianity speaks a language only a few understand.

In trial after trial, all the participants tried the win-lose scenario of cornering the market on chips. Because the win-lose scenario was easier to play but almost impossible to achieve, no one ever won the game. Even when individuals began noting this, they still played the win-lose scenario simply because the other players were. Now the win-win scenario required some foresight and thinking to achieve, but could be accomplished far more easily than the win-lose outcome. Yet time and again players refused to play the win-win game even though it was actually more challenging and fun to play. A clear winner and loser were necessary. Darwinism’s conceit is that it speaks to the natural, unredeemed man fluently, while Christianity speaks a language only a few understand.

Because of this, Darwinism plays well in America because our country’s story is founded on people pulling themselves up by their own bootstraps—at least that’s the common interpretation. But historians will tell you that the American story is truly one of outstanding cooperation toward common goals. Yet we hear the “self-made man” mantra over and over to the detriment of the real story.

American business has undermined capitalism informed by a Christian worldview by substituting Darwinism at the base. Companies too often play like the individual at the game table trying to corner the market. “I win, you lose.” While some people may think this is the whole point of capitalism, rather it’s the whole point of the Darwinism that we exchanged for Christ’s mandate of “win-win.” By its very nature, Darwinism’s win-lose functionality creates a class-structured society and amplifies its extremes. At its most pure, Darwinism’s selfishness only promotes two classes: winners and losers. Win-win is off the radar.

The only possible outcome of selfishness is greed; the selfish can never have enough.

I read The Wall Street Journal nearly every day. Over the last five years I’ve noticed an astonishing trend. Time and again I would read snippets of corporate quarterly announcements that went something like this:

XYZ Industries today announced record profits for the quarter ending June 30th. The $107 million windfall is a 31% increase over this quarter last year. “Mining new markets has been the key,” said J.J. Shekel, CFO. “Our Asian strategy has allowed us to leverage niches in China that previously had been shuttered by internal government squabbles.” XYZ Industries also reported that it will undergo a 3,000 person reduction in force by the end of the year. “We must compete in a global space and only a leaner XYZ is able to do so,” Mr. Shekel concluded.

The WSJ usually has about a dozen of these little business reports every day. On one day alone, I counted three companies that reported record profits, but then added they’d be downsizing the very people that got them those record profits.

For the selfish corporate gene, nothing matters—even people—as long as the gene survives till next quarter. That’s a win-lose mentality. And its Darwinian rationale is always that the downsized employees will get on better somewhere else. And if they don’t, well, the company doesn’t want to hear about it because, well, it’s bad for corporate karma.

When XYZ Industries prefers record profits over its own people, expediency is at the base of the reasoning. “We made it with 7,000 employees; we can make it with 4,000.” No one is asking if a better way exists that might take time to achieve, but would be win-win for the company and ALL its employees. (I’ll talk about this win-lose devaluation of people when I discuss Jack Welch in the coming analysis of Downsizing.) Noted in the previous entry in this series, Binding the Business Strongman, the wholesale replacement of Christian workplace practices with Darwinian thought has rendered all business practices short-term. Companies are simply interested in what happens quarter over quarter. As long as they can demonstrate to shareholders that they’ve profited in a quarter, everyone looks the other way.

A Christian worldview doesn’t operate this way. Christianity is an eternal view; it is lasting and thinks about permanence. But the mantra of business today is “Adapt or die.” (Notice the Darwinian terminology!”) The obvious problem with this concerns what exactly needs to be changed and in what timeframe. The problem facing business is that the quarterly nature of business processes means change has to be implemented rapidly. This leads to natural short-sightedness and a “Me, too” practices mentality. Plenty of damage results.

Dell Computer is a perfect example of how to do it wrong. Long the high-flyer in the computer biz, Dell stumbled badly when it moved all its support call centers to India. However, knowledgeable business customers did not want to talk to a tech in India reading a pat answer off an internal Web page; they wanted to talk with someone who actually troubleshot computers and software. Nor did they like having their telephone rep call himself “Mike” when it was obvious his name was more likely Rajneesh. Dell’s business customers had a fit and Dell was forced to move at least one call center back to the United States in the wake of corporate customer defections.

The problem here is that Dell fell into the conventional short-term Darwinian wisdom. Instead of asking the Christian worldview question, “What is best for our customers long-term?” they asked “What is everyone else doing to save money right now and how quickly can we join that crowd?” And they got burned by it by insulting their most informed (and most cash-rich) customers.

This has been a considerable amount to digest, so I’ll cut it short here. We’ll continue looking at the rest of the list of issues in the next installment of this series, The Redemption of Corporate America, Part 2.

Previous post in this series: The Christian & the Business World #7: Binding the Business Strongman

Next post in this series: The Christian & the Business World #9: The Redemption of Corporate America, Part 2

In one of the most damning articles I’ve ever read, The Wall Street Journal in July 2002 drew a correlation between the leadership of those disgraced companies and their (largely Evangelical) church affiliations. But Ebbers and Lay were not the only two Evangelical Christians to find themselves having to answer to the courts and shareholders for their fraudulent schemes. From the lowliest person involved in one of these well-known business scandals to the highest echelons of those disgraced companies, Christians were involved every step of the way promoting gross fraud and chicanery.

In one of the most damning articles I’ve ever read, The Wall Street Journal in July 2002 drew a correlation between the leadership of those disgraced companies and their (largely Evangelical) church affiliations. But Ebbers and Lay were not the only two Evangelical Christians to find themselves having to answer to the courts and shareholders for their fraudulent schemes. From the lowliest person involved in one of these well-known business scandals to the highest echelons of those disgraced companies, Christians were involved every step of the way promoting gross fraud and chicanery. The man who works there, worships there,” it wasn’t given much fuss.

The man who works there, worships there,” it wasn’t given much fuss.