Juvenile delinquency and young women falling prey to the vice of the city—both were created due to massive shifts in the work lives of Americans during the Industrial Revolution. Both saw the Church in this country rise to meet the challenge.

Juvenile delinquency and young women falling prey to the vice of the city—both were created due to massive shifts in the work lives of Americans during the Industrial Revolution. Both saw the Church in this country rise to meet the challenge.

In the case of the young women, in 1877 a relatively new organization, the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), stepped in to address the need. Seeing that many unmarried women were fleeing the farms in search of a better life in the city (or were part of the immigration stampede into the country), the YWCA decided to proactively deal with the problem of unskilled women moving into the city. Foresight proved them correct. The newly invented typewriter was a huge draw for women looking for decent work, and the YMCA started offering classes in the use of the device. These classes were remarkably popular and the pool of trained secretaries in the major cities was largely due to the YWCA. That organization also saw to the spiritual needs of the women, as well as to housing, medical provisions, and keeping oneself pure in a business environment that was so new that the rules were still being written even as the YWCA was teaching them.

The alternative for single women flooding into the city was often prostitution and the YWCA understood this. By meeting a great need, they were able to help keep women on a straight moral path and provide for food, shelter, and spiritual growth. This is the Church making the best of what could have been an awful situation.

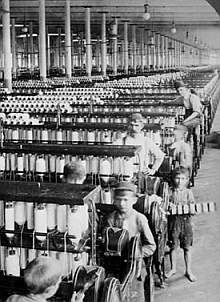

This flight also contributed to the problem of delinquency. Once an important cog in the home economy, teenagers were left with nothing to do once farms were abandoned and factory reforms prevented the younger ones from working. Restless, farm-flight and immigrant children proved that idle hands were the devil’s play things. Crime rocketed up in the cities. The Church’s answer was a new idea: What if a ministry was founded that focused solely on the needs of youth?

Despite many years of research, I have not been able to pin down the exact date that a genuine youth-only ministry within a specific church first hit the spotlight. The first parachurch youth ministry of consequence was, interestingly enough, the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) in Britain in the 1840’s, created by George Williams specifically to address the vagrancy of young men who, in this case, did have jobs in the factories, but were without family or away from home and were missing a fulfilled life. The YMCA grew rapidly and spread to America, only to be depleted by the Civil War as young men marched into battle. After the war, one of the major proponents of the YMCA, which was by all accounts not beholden to any one church, was evangelist Dwight Moody. His fame helped spread the YMCA vision of “The improvement of the spiritual, mental, social and physical condition of young men.”

From the parachurch YMCA, the focus began to drift back to churches in smaller locales that couldn’t afford a YMCA; some started their own ministries to youth. This helped further propel the whole concept that youth were a new ministry demographic. All this came about through the societal changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution. By the time Youth for Christ was popular in the 1940s, the idea that youth ministry was essential to the Church was a given.

But there are larger issues at work here.

Training women to have meaningful work in order to avoid a dissolute life is the Church meeting a practical business need while fending off corrupt social forces. On the other hand, youth ministry had its start in changes in the social fabric in Britain and America, then extended those to the spiritual. There is a very subtle distinction here.

Youth ministry’s long-term effect has been to take a family already fractured by societal changes caused by business practices coined during the Industrial Revolution and fracture it even further. While there is no doubt that on a granular level youth ministry has been effective in the lives of individuals (I include myself here), studies by researchers like George Barna have shown that, on the whole, the net effect of youth ministry today has been negligible on the spiritual and emotional welfare of youth. Christian youth are so much like their peers who don’t aspire to any Christian leanings as to be virtually indistinguishable. This is further proven by the horrendous attrition rate among Christian young people once they hit college. The majority come out of college completely stripped of whatever Christian faith and practice they possessed going in. Obviously, one must ask why this is if youth ministry were truly equipping youth to withstand the barrages of our cultural death-throes. We must consider whether the youth ministry model that was initially developed more than a hundred and sixty years ago is still valid.

The problems of youth ministry are compounded by the fact that it eventually sought to distance itself from conventional, whole-family ministry. In its infancy, youth ministry attempted to make the best of a bad situation in the lives of youth living far from home, but this is no longer the case. Most youth ministries in churches today appear to pride themselves on the fact they offer teens a chance to get away from their families and hang out with other teens. The net effect here has been that the typical youth minister has become the substitute parent for many teens. Since youth ministry tends to have its own separate teaching component, the incidental effect has been that parents have abdicated the Christian teaching role for their teens. This further alienates family members and leads to a loss of parental authority and respect.

The Industrial Revolution was responsible for the initial splits within family. The home economy that kept both parents at home working, supported by their children, was disrupted by changes in work emphasis and the rise of big business. Dads started working distantly and were gone for most of the day. This put added stress on moms to hold the family together. As work shifted to the cities, young people heard the siren call and left their traditional responsibilities behind. For farm families, this shattered the procession of farm life from one generation to another and hastened the move to cities. Youth moving to the cities encountered vice and the Church responded.

The larger question here that is left unanswered is whether the response of the Church was correct.

On the surface, the YWCA’s training of young women for secretarial work in light of the rise of business in the cities is admirable. They certainly addressed the need and were smart in doing so. But that larger question looms, particularly in the light of more than a hundred years of wisdom asks whether the Church missed the big picture for the details.

Even today, the Church is not asking whether the Industrial Revolution broke something, not only in society, but in the Church. In many ways, the Industrial Revolution was already in its maturity before the Church responded to it. Worse, still—and even today—no one in the Church in America is asking if the Industrial Revolution has a fundementally evil component that the Church swallowed without thinking. The Church certainly responded to the most obvious societal ills created by the Industrial Revolution as we have seen in part here, and while that was admirable, the results have been mixed.

In the next installment, The Industrial Church Revolution, Part 3, we’ll examine the “Jesus as CEO” concept that gained popularity in the 1920s and 30s along with Social Darwinism’s pernicious effects on the Church and business.

And thanks for reading this series!

Previous post in the series: The Christian & the Business World #4: The Industrial Church Revolution, Part 1

Next post in the series: The Christian & the Business World #6: The Industrial Church Revolution, Part 3

And though it worked, it wasn’t until James Watt radically improved the design in 1769 that the first rumblings of pressure surfaced that would seal the fate of that storybook lifestyle of Mom and Pop Free America.

And though it worked, it wasn’t until James Watt radically improved the design in 1769 that the first rumblings of pressure surfaced that would seal the fate of that storybook lifestyle of Mom and Pop Free America. And a little book called “On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection” hit the shores of America.

And a little book called “On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection” hit the shores of America. In this way, God viewed His Man as a partner for achieving His will.

In this way, God viewed His Man as a partner for achieving His will.