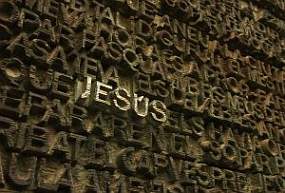

Yesterday, I mentioned the E-word: evangelism.

That’s not a fun word in a lot of American Christian circles. In the secular world, the fear of speaking in front of a crowd of people scares the willies out of more people than anything else. Obviously,  no one is polling Christians on fear of evangelism or else you’d see 90 percent of believers’ knees knocking together at the mere mention of the word.

no one is polling Christians on fear of evangelism or else you’d see 90 percent of believers’ knees knocking together at the mere mention of the word.

In America at least, I see the issue of our lousy attitude toward evangelism breaking down into two camps, the Haves and Have Nots.

If you are a Have, then life treats you well. You applied your nose to the grindstone and not only came away with your nose intact, but a two-car garage full of nice things as well. You’re healthy and so are the rest of the people in your family. As they say, it goes well with you. People point to you and say, “There goes a success.” And you are a success, at least as far as the world goes. You have the material gain, the nice semi-upper-level job, and the 2.3 children in an exclusive private Christian school to prove it. Your money gets you out of every jam you might find yourself in. And some Sundays, when you remember, you thank God for all the stuff He has given you.

If you are a Have Not, you look at those who live in the tony Have planned community down the road and pray that, for your sake, they discover Freecycle—and soon.Your car is ten years old and visited the shop one time for each of its years last year, each visit bringing a different mechanical ailment. You suffer from a vague unease that perhaps you have hidden sin in your life that prevents you from being a Have, yet you can never discover what that sin might be. The bills never seem to stop piling up. When your family talks about its situation, the phrase “make do” comes up a lot. In church on Sunday, you worry that people are thinking your nice church clothes are looking a little threadbare.You sometimes wonder if God plays favorites.

For the Have and the Have Not, the mere mention of evangelism brings on an attack of hives.

Why?

In the case of the Have, evangelism forces reckoning. It brings to the surface the reality that you claim to follow an invisible god-man who died and rose from the grave. You talk to this god-man through something called prayer. You eat his body and drink his blood. You use lingo found only within that group of people who do the same. That god-man asks things of you that “normal” people aren’t required to do, like take care of the naked and the prisoner. Evangelism is the means by which you want others to live that same way and follow that same god-man.

When you’re a Have, doing just that is a little unnerving. Because it makes you look weird. It casts a pall over your otherwise normal American life. It reminds you that the things that god-man said make other people uncomfortable, people who can make or break your career, people who can send you back where you came from, and you just don’t want to go back there because it wasn’t even a shadow of the life you enjoy now. Losing your Have-ness would be the same as dying—or worse.

So you leave the evangelism to others.

In the case of the Have Not, evangelism reminds you of failure. How many have come to Jesus because of your direct involvement in their lives? Not many. And why would they? You don’t have much. You’re not the shining example of the American Dream. There’s a vague unease that perhaps God is not blessing you as much as He is blessing others. Your pastor tells you that evangelism is nothing more than telling someone else what Jesus has done for you. Yet by the normal American standard of blessing, you’re not doing that well. Your pagan neighbors are, so why would they want to come down in the world? Why would they want to be a Have Not when they may very well be a Have right now?

When you’re a Have Not, you sometimes feel like an embarrasment to the Kingdom of God, the red-headed stepchild, the third wheel. Your Have-Not-ness disqualifies you from evangelizing because who really wants to be like you? Why would someone want to follow a god who has such a mediocre disciple working for him? Who wants to tell prospective followers that they may come down in their station in life if they follow Jesus? Or that devils may try to attack them more fiercely so that they’ll face discouragement in a way they never have before, discouragement that threatens to send them back to where they were before coming to Jesus but with all of the former things of that life now lost.

So you leave the evangelism to others.

The funny thing about the Haves and Have Nots here in the American Church is that it’s the Have Nots that are the most deluded. Truth is, most everyone in America is a Have, while most of the rest of the world is a Have Not. And oddly enough, the greatest revivals and most effective evangelism are coming out of those places in the world that practically define what it means to be a Have Not. Except that those Have Not Christians in those Have Not countries could not have more joy because they are Haves in the one thing that truly matters, having Jesus.

For the Haves, there is one thing they lack. If they were to read their Bibles, they would know what that one thing is. The problem for the Haves is that they love their Having more than they love their own souls—or the One who can save those very souls. Evangelizing others reminds them of this truth. It’s why they avoid it like the plague.

Times are coming and may already be here when the Haves will find themselves having less. Maybe that will change their attitude toward evangelism. Or maybe it will just make them bitter. That’s hard to predict. Sliding into the Have Nots is a foreign feeling. The Haves won’t know the language or customs of what it means to dwell in the Land of Have Not. I suspect some may find God’s grace in that Land, though.

At least, that’s what I’m praying.

No matter which camp you fall into, it’s time to live differently. The harvest is plentiful and the laborers are few. And if you look closely enough, you can see that today is a shade darker than yesterday.

Though we serve a big God, no shield is large enough to keep out the world.

Though we serve a big God, no shield is large enough to keep out the world.