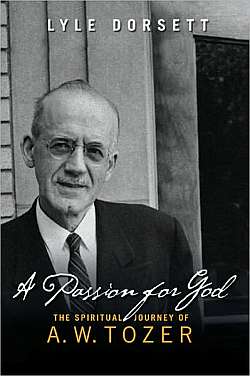

I’d like to continue the theme on charismata by offering wisdom from A.W. Tozer, the “patron saint” of Cerulean Sanctum. When Tozer preaches, I can’t help but be moved, nodding my head to every word. He understood the Lord in a way few of us do today, and his prophetic voice still rings loudly in the ears of modern Christians.

Are we listening?

Here is Tozer from his book Paths to Power: Living in the Spirit’s Fullness :

***

Break up your fallow ground, for it is time to seek the Lord, till he come and rain righteousness upon you.

—Hosea 10:12

HERE ARE TWO KINDS OF GROUND: fallow ground, and ground that has been broken up by the plow.

The fallow field is smug, contented, protected from the shock of the plow and the agitation of the harrow. Such a field, as it lies year after year, becomes a familiar landmark to the crow and the blue jay. Had it intelligence, it might take a lot of satisfaction in its reputation; it has stability; nature has adopted it; it can be counted upon to remain always the same while the fields around it change from brown to green and back to brown again. Safe and undisturbed, it sprawls lazily in the sunshine, the picture of sleepy contentment.

But it is paying a terrible price for its tranquility: Never does it see the miracle of growth; never does it feel the motions of mounting life nor see the wonders of bursting seed nor the beauty of ripening grain. Fruit it can never know because it is afraid of the plow and the harrow.

In direct opposite to this, the cultivated field has yielded itself to the adventure of living. The protecting fence has opened to admit the plow, and the plow has come as plows always come, practical, cruel, business-like and in a hurry. Peace has been shattered by the shouting farmer and the rattle of machinery. The field has felt the travail of change; it has been upset, turned over, bruised and broken, but its rewards come hard upon its labors.

The seed shoots up into the daylight its miracle of life, curious, exploring the new world above it. All over the field the hand of God is at work in the age-old and ever renewed service of creation. New things are born, to grow, mature, and consummate the grand prophecy latent in the seed when it entered the ground. Nature’s wonders follow the plow.

There are two kinds of lives also: the fallow and the plowed. For examples of the fallow life we need not go far. They are all too plentiful among us.

The man of fallow life is contented with himself and the fruit he once bore. He does not want to be disturbed. He smiles in tolerant superiority at revivals, fastings, self-searchings, and all the travail of fruit bearing and the anguish of advance. The spirit of adventure is dead within him.

He is steady, “faithful,” always in his accustomed place (like the old field), conservative, and something of a landmark in the little church. But he is fruitless. The curse of such a life is that it is fixed, both in size and in content. To be has taken the place of to become. The worst that can be said of such a man is that he is what he will be. He has fenced himself in, and by the same act he has fenced out God and the miracle.

He is steady, “faithful,” always in his accustomed place (like the old field), conservative, and something of a landmark in the little church. But he is fruitless. The curse of such a life is that it is fixed, both in size and in content. To be has taken the place of to become. The worst that can be said of such a man is that he is what he will be. He has fenced himself in, and by the same act he has fenced out God and the miracle.

The plowed life is the life that has, in the act of repentance, thrown down the protecting fences and sent the plow of confession into the soul. The urge of the Spirit, the pressure of circumstances and the distress of fruitless living have combined thoroughly to humble the heart.

Such a life has put away defense, and has forsaken the safety of death for the peril of life. Discontent, yearning, contrition, courageous obedience to the will of God: these have bruised and broken the soil till it is ready again for the seed. And as always fruit follows the plow. Life and growth begin as God “rains down righteousness.” Such a one can testify, “And the hand of the Lord was upon me there.”

Corresponding to these two kinds of life, religious history shows two phases, the dynamic and the static.

The dynamic periods were those heroic times when God’s people stirred themselves to do the Lord’s bidding and went out fearlessly to carry His witness to the world. They exchanged the safety of inaction for the hazards of God-inspired progress. Invariably the power of God followed such action. The miracle of God went when and where His people went; it stayed when His people stopped.

The static periods were those times when the people of God tired of the struggle and sought a life of peace and security. Then they busied themselves trying to conserve the gains made in those more daring times when the power of God moved among them.

Bible history is replete with examples. Abraham “went out” on his great adventure of faith, and God went with him. Revelations, theophanies, the gift of Palestine, covenants and promises of rich blessings to come were the result. Then Israel went down into Egypt, and the wonders ceased for four hundred years. At the end of that time Moses heard the call of God and stepped forth to challenge the oppressor. A whirlwind of power accompanied that challenge, and Israel soon began to march. As long as she dared to march God sent out His miracles to clear the way for her. Whenever she lay down like a fellow field He turned off His blessing and waited for her to rise again and command His power.

This is a brief but fair outline of the history of Israel and of the Church as well. As long as they “went forth and preached everywhere,” the Lord worked “with them,…confirming the word with signs following.” But when they retreated to monasteries or played at building pretty cathedrals, the help of God was withdrawn till a Luther or a Wesley arose to challenge hell again. Then invariably God poured out His power as before.

In every denomination, missionary society, local church or individual Christian this law operates. God works as long as His people live daringly; He ceases when they no longer need His aid. As soon as we seek protection out of God, we find it to our own undoing. Let us build a safety-wall of endowments, by-laws, prestige, multiplied agencies for the delegation of our duties, and creeping paralysis sets in at once, a paralysis which can only end in death.

The power of God comes only where it is called out by the plow. It is released into the Church only when she is doing something that demands it. By the word “doing” I do not mean mere activity. The Church has plenty of “hustle” as it is, but in all her activities she is very careful to leave her fallow ground mostly untouched. She is careful to confine her hustling within the fear-marked boundaries of complete safety. That is why she is fruitless; she is safe, but fallow.

Look around today and see where the miracles of power are taking place. Never in the Seminary where each thought is prepared for the student, to be received painlessly and at second hand; never in the religious institution where tradition and habit have long ago made faith unnecessary; never in the old church where memorial tablets plastered over the furniture bear silent testimony to a glory that once was. Invariably where daring faith is struggling to advance against hopeless odds, there is God sending “help from the sanctuary.”

In the missionary society with which I have been associated for many years. I have noticed that the power of God has always hovered over our frontiers. Miracles have accompanied our advances and have ceased when and where we allowed ourselves to become satisfied and ceased to advance. The creed of power cannot save a movement from barrenness. There must be also the work of power.

But I am more concerned with the effect of this truth upon the local church and the individual. Look at that church where plentiful fruit was once the regular and expected thing, but now there is little or no fruit, and the power of God seems to be in abeyance. What is the trouble? God has not changed, nor has His purpose for that church changed in the slightest measure. No, the church itself has changed.

A little self-examination will reveal that it and its members have become fallow. It has lived through its early travails and has now come to accept an easier way of life. It is content to carry on its painless program with enough money to pay its bills and a membership large enough to assure its future. Its members now look to it for security rather than for guidance in the battle between good and evil. It has become a school instead of a barracks. Its members are students, not soldiers. They study the experiences of others instead of seeking new experiences of their own.

The only way to power for such a church is to come out of hiding and once more take the danger-encircled path of obedience. Its security is its deadliest foe. The church that fears the plow writes its own epitaph; the church that uses the plow walks in the way of revival.

***

Amen, Dr. Tozer, amen.

If I were to examine my life and discover what man has contributed more to my own spiritual growth, it would be no stretch to say that Aiden Wilson Tozer has enlarged my knowledge of God in great ways. No other Christian author has made me think and weep like Tozer has, and I believe I would not be writing this blog if not for him. In fact, I may not have been very much of a Christian presence anywhere if it were not for Tozer.

If I were to examine my life and discover what man has contributed more to my own spiritual growth, it would be no stretch to say that Aiden Wilson Tozer has enlarged my knowledge of God in great ways. No other Christian author has made me think and weep like Tozer has, and I believe I would not be writing this blog if not for him. In fact, I may not have been very much of a Christian presence anywhere if it were not for Tozer. He is steady, “faithful,” always in his accustomed place (like the old field), conservative, and something of a landmark in the little church. But he is fruitless. The curse of such a life is that it is fixed, both in size and in content. To be has taken the place of to become. The worst that can be said of such a man is that he is what he will be. He has fenced himself in, and by the same act he has fenced out God and the miracle.

He is steady, “faithful,” always in his accustomed place (like the old field), conservative, and something of a landmark in the little church. But he is fruitless. The curse of such a life is that it is fixed, both in size and in content. To be has taken the place of to become. The worst that can be said of such a man is that he is what he will be. He has fenced himself in, and by the same act he has fenced out God and the miracle.