We may all have heard the statistics:

- More heart attacks occur in December than any other month

- More people are treated for depression in December than any other month

What is it about this time of year that people are so stressed, so sad?

I’ll admit that Christmastime has not been the same for me since my parents died. My father died at Christmastime five years ago, and Mom was clearly terminal, living with us, but in many ways already gone.  The following Christmas in 2001 drove home the fact , now that they were both gone, that they had borne a far greater role in the joy of the season for me than I had understood. You are always a child at Christmastime as long as you’ve got a surviving parent, but take that away and now it’s up to you to be the one who maintains the Christmas spirit. Now it’s for your children more than for you. It’s a role we never think about accepting until it is thrust upon us and there is no one else to turn to.

The following Christmas in 2001 drove home the fact , now that they were both gone, that they had borne a far greater role in the joy of the season for me than I had understood. You are always a child at Christmastime as long as you’ve got a surviving parent, but take that away and now it’s up to you to be the one who maintains the Christmas spirit. Now it’s for your children more than for you. It’s a role we never think about accepting until it is thrust upon us and there is no one else to turn to.

Big families make up for some of that loss, but Christmas is a bit sad for me now because I see that my own little family is probably going to stay little. The dynamic of having brothers and sisters at Christmastime will be lost on my son, something I never thought would be the case when my wife and I got married, but that is how things are, quite apart from our best intentions. Just the three of us creates a certain vulnerability at Christmastime that is hard to explain. I had my brothers around growing up, but my son will probably just have us.

Today, I was going to bake cookies, but my son may have chickenpox and my wife is very sick. Illness at Christmastime is the worst time for being under the weather. I remembered a couple Christmases growing up when one of my family was sick, but that was rare. However, in the last few years someone has always been sick at Christmas, usually me. When we were excited about hosting my wife’s family for Christmas a couple years ago, the real flu hit just about everyone and the whole enterprise shriveled up because no one was in the mood to do anything. The whole house should have been quarantined. Lots of planning and effort, but not much realization.

Whatever planning I had this year didn’t materialize. We can’t go see my brother across town for Christmas because he and his wife are expecting a child any day now and chickenpox and ready-to-birth moms are an absolute no-no. I had great plans for my wife and I to wrap presents together this year and relax, but she is in bed sick, and with my meager present-wrapping skills, I labored for six hours over what amounted to a little more than a dozen presents. Doing things alone at Christmas is not how it should be.

That meager stack of presents isn’t how it should be, either. I grew up with a Christmas tradition that said that Dec. 25th was the day that you got everything you were going to get for the year. All the toys came then. Most of the clothes came then. As a result, Christmases were huge at our house. Despite having a large family room, between the genuine tree and the tsunami of gifts pouring out from under it, there was hardly room to walk. I loved to shop for people, too, being one of those people who got more excited by what he gave then by what he received. I always tried to think of marvelous gifts to give, and more often than not, those gifts were spectacular and exactly the right thing to for each person.

Today, though, financial considerations have cut back our Christmases to the point that whatever boost I got from giving has been dampened by the realization that few of the things I’d like to give are within our reach anymore. If there’s a tree, it swallows whatever may be under it. And every year we are asked to cut back even more. Two out of the last five Christmases found us without an income, vulnerable at the one time of the year when plenty is assumed. Those were hard. I’m not sure I ever really got over them, either. You wonder what the next Christmas holds, a bit more fearful than the Christmas before.

None of this is how it should be. It’s not how I remember Christmas.

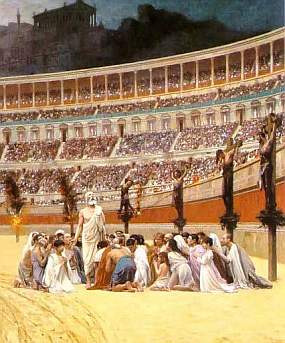

For four hundred years, the world lay waiting. There was no word from the Lord. The pagans swept in, and with them came darkness. Medes, Persians, Babylonians, Romans—one horde after another asserted control over the people of God.

Then came the light, the promise, the hope.

Christmas is a sad time for many who remember that it was good once, but doesn’t seem that way anymore. They are the ones who cry out, “Maranatha!” Christmas reminds us of all that should be right with the world, but the world isn’t always right. And as time goes on, it seems a little less right every year. It is our groaning, awaiting something better, the second Advent.

Nostalgia can bring paralysis. When I see people paralyzed by Christmastime, I know how they got that way. If you had a great childhood and things aren’t so great now, Christmas is missing that spark of life. An emptiness resides where the expectation once lived, nagging and frustrating.

But it’s not about Christmas, is it? It’s about an empty tomb. Christians were never the Christmas people, those concentrated on the First Advent. No, we are the resurrection people, born to die, then to live again. And at this point in time, as we move farther away from our own birth and closer to the time of our own death, we live in that stasis between the two, caught between opposing worlds, to die to the one and be raised into the other.

No one said it would be easy walking out that dying. When I look at Christmas 2005, I see a lot of little deaths. In the midst of that sadness, though, is the hope of the world to come.

If you’re sad this Christmas, let someone else know. It’s not something you struggle with alone—millions of others have a heavy heart as the shortest days of the year roll around. Don’t bear that by yourself.

…but we ourselves, who have the firstfruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we wait eagerly for adoption as sons, the redemption of our bodies. For in this hope we were saved. Now hope that is seen is not hope. For who hopes for what he sees? But if we hope for what we do not see, we wait for it with patience.

—Romans 8:23b-25 ESV

from what I've personally heard. The older the commenter gets, the more likely this issue sticks in his craw.

from what I've personally heard. The older the commenter gets, the more likely this issue sticks in his craw. for the crime of printing Bibles for the Chinese people to read.

for the crime of printing Bibles for the Chinese people to read.