Anyone who reads this blog knows that I have little patience for attempting to run churches by business principles. That’s been weighed in the scale and found wanting every time it’s been attempted.

Last evening, as I was prepping for an interview I was to conduct with a supply chain expert for one of the world’s most notable companies, I brushed up on William Edward Deming.

Deming had a handful of adherents here in the States, but he was practically deified in Japanese corporations. While his ideas on efficiency and productivity were toyed with elsewhere, the Japanese latched on and rode Deming’s ideas to the top. Acceptance of Deming is why Toyota has thrived, while rejection of his principles is epitomized by GM execs groveling on Capitol Hill.

Deming’s theories include 14 main principles, all of which are intriguing. To me, none grabs like this one:

Eliminate slogans, exhortations, and targets for the work force asking for zero defects and new levels of productivity. Such exhortations only create adversarial relationships, as the bulk of the causes of low quality and low productivity belong to the system and thus lie beyond the power of the work force.

Translation: If the system is broken, it’s a waste of time asking more from the laborers. Instead, fix the system.

I look at this statement of Deming’s not as a prescription, but as an astute observation. Therefore, we can learn from it as Christians without trying to run our churches by it.

When I watch the American Church in action, what passes for leadership is little more than slogans, exhortations, and targets tied around the necks of people who cannot possibly meet leadership’s criteria because they labor in a broken system. Yet who is tackling the broken system? Who is that brave?

You would think Christians, of all people, should be, right?

I believe the singular failure of Evangelicalism in our lifetimes can be tied to its leaderships’ inability to speak to broken systems. Those leaders did not address economics, justice, relationships, work, politics, or anything else from a systemic perspective. As a result, despite the fact that our God is a consuming fire, we have brought His powerful Truth to bear on the fringes, not on the core presence of wicked systems. It’s like using a sword to clean under one’s fingernails, or wielding a napalm-based flamethrower to toast marshmallows. The sword and the flamethrower are intended to do battle with dire enemies, not with a clod of dirt or the raw middle ingredient of a s’more.

The culture wars are one example of the resulting massive failure. For instance, teen pregnancy is a serious issue, but have we addressed it systemically? Or have we fought it with slogans, exhortations, and targets?

Sadly, our leaders neither waged that battle on a systemic level, nor did they even bother to ask the right questions. (Why? Because those tough questions beg for tougher answers, ones that may ask much of the askers.) In the case of the teen left unsupervised at home after school, why not question why both mom and dad are working? Or ask what it is about the way we work that may make for more children born to teens? Instead, unwilling to tackle the systemic issues of why our society labors as it does, Christian leaders opted for the path of least resistance—and least success.

But it doesn’t have to be that way.

Christianity provides a unified answer for the whole of life.

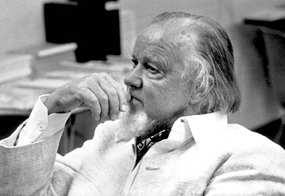

—Francis Schaeffer

I have always enjoyed reading Schaeffer because he tried to speak to the Church about more than just eliminating defects in the individual or boosting spiritual productivity.  He understood that Christians must address broken systems. Unless the Christian brings truth to bear on systems, most larger changes will be superficial—or nonexistent.

He understood that Christians must address broken systems. Unless the Christian brings truth to bear on systems, most larger changes will be superficial—or nonexistent.

Kingdoms are built on systems. The world has its kingdom system and God has His. In the clash of kingdoms, systems must be overthrown for one kingdom to displace the other. Yet where are the Christian leaders who are waging war against systems? Where are the Schaeffers of 2009? It’s been nearly a quarter century since he died, and as far as I can tell, he’s had no successors. And the Church continues to suffer for this lack.

Want to truly change the world for Christ? Start asking tougher questions about the way the world systems work, then bring the Gospel light to bear on the very heart of their darkness.

Now, who out there is going to do just that?

In the last couple days, I’ve looked at some problems the Church in America faces in addressing financial crises.

In the last couple days, I’ve looked at some problems the Church in America faces in addressing financial crises.