I’ve got no strings

To hold me down

To make me fret, or make me frown

I had strings

But now I’m free

There are no strings on me

Hi-ho the me-ri-o

That’s the only way to go

I want the world to know

Nothing ever worries me

I’ve got no strings

So I have fun

I’m not tied up to anyone

They’ve got strings

But you can see

There are no strings on me

If you don’t remember that ditty from your childhood (or parenthood), it’s sung by Pinocchio in the classic Disney film.

I hear this song a lot lately. As I’ve listened to the Church in America over the years, I hear it voiced by a growing group of Christians who are ecstatic that they’ve dropped out of the institutional Church.

You know these folks. They talk about how much freer they are now that they no longer attend Sunday morning services. Now that they’re not part of a local assembly, they talk about all the things they can do for the Lord that they could not do before or were made to feel guilty for doing by the institutional Church police. Theirs is a louder and louder voice.

I was almost one of those people. Fed up with the way churches operated, I wanted to mold a loose affiliation of church-shunners who felt exactly as I did, a hand-chosen group of friends who could pal around together in Christ and buck the established institutional system that had grown so lethargic and monolithic. Strings? I didn’t want to have any strings on me, especially institutional Church strings.

But as I have mellowed in the last few years, I have come to realize the problem of being unstrung.

An unwillingness to be herded plagues the American psyche . As the world’s iconoclasts, no one has the right to tell us what to think or how to behave. If we don’t like something, no force from heaven or hell can dissuade us. Rugged individualism defines us. We are the ultimate bootstrappers, devoted to me, myself, and I. I don’t need you and you don’t need me, and that’s the way the American religion works.

Strange as it may seem, that same mentality reigns in those people who deem the institutional Church unworthy. And just as I cannot support the errors of the American religion, I am fully convinced that abandoning the traditional church in this country is a grave mistake.

When the Lord formed His Church after Pentecost, it was a ragtag group of misfits. You had widows, orphans, Roman politicians, prostitutes, Jewish zealots—the ultimate mishmash of classes, races, and temperaments. And that’s exactly how God desired the Church to be.

Can you imagine what it must have been like for the Pharisee who had just come to Jesus to sit down with whores and Romans? How stretched, right? Do you think that man grew on the inside?

When one of us decides that we don’t want to be a part of the traditional local church, we lose something exceptionally valuable: the test of dealing with people we may not especially like.

We see a bit of this in the consumeristic action of church shopping. We hop and shop from church to church looking for one that best fits our desires, the one filled with people most like us. (Oddly enough, people who eschew the institutional Church are often the most vocal against church shopping. )

At a time in American history when it seems as if everyone considers himself or herself a victim, when we walk around as open wounds expecting some jerk to pour salt on us, when intelligent debate is no longer possible between people without the wailing and gnashing of teeth, and other people just plain suck, people who drop out of church only add fuel to that fire of misanthropy.

So while some may think they are truly spiritual by saying goodbye to what most of us recognize as church, I wonder if those dropouts are missing out on vital, God-ordained character building.

A few years ago, David Wayne of Jollyblogger interviewed a pastor from the country of Georgia. When David asked that pastor about church shopping and hopping, the pastor was shocked. In his country, church people were born into a church and were buried in its cemetery. What about discord and disagreements? David wondered. The pastor gave a simple answer: People were forced to work out their differences because they were fellow members of the Body of Christ.

When Christians drop out of church, we shun the vital truth that Christian character is built on dealing with one’s differences within a body of believers comprised of people who are not exactly like us. In fact, we may not even like many of those people.

But the Kingdom of God does not allow us to pick and choose who will be in it. God desires us to learn how to live with people who would ordinarily bug the heck out of us. That is part of our growth as Christians.

When I see people dropping out of church and proclaiming how free they now are, I can’t help but think that their supposed freedom comes at a steep cost,  the cost of learning to find common ground with people they would not have chosen to be in their Christian clique.

the cost of learning to find common ground with people they would not have chosen to be in their Christian clique.

Pinocchio had a cranium filled with sawdust when he sang how free he was from being tied to anyone. Is that how we wish to be?

When I hear people who have dropped out of church, they almost invariably talk about how they now get together with their handpicked friends, people just like themselves, for fellowship. I find that sad because I gain valuable lessons in my inner man when I must deal with a wide swath of diverse fellow believers I did not handpick.

God desires that I learn to love brothers and sisters in Christ who are ignorant, lazy, judgmental and stubborn—which may even be how others perceive me. He also desires that I share in the lives of people who are much smarter, more loving, and deeper in the faith than I am—people I might ordinarily avoid because they make my own walk with Christ appear so tepid.

Would I choose to hang with Christian 80-year-olds, sports nuts, quilters, teens, auto mechanics, infants, and the like if it were not for the institutional Church? Probably not, but God asks me to anyway, forcing the issue by keeping me in the local church.

No matter where others fall on the spectrum of Christian maturity and social graces, all have something to teach me that is valuable. And I have in them people whose problems I might not ordinarily encounter, but for whom Christ desires I intercede and bear burdens. It is in those burdens found in people who are not like me at all that I learn what it means to seek all solutions in Christ alone.

The world around us is fragmenting into tribes, and God help us all when tribes clash. But the Church is not to be this way. We are called to get along, no matter what our fellow Christians may be like.

Sadly, when we drop out of church and go our own unstrung, “enlightened” way, we avoid this lesson. And we are poorer in spirit for doing so.

Blest be the tie that binds

Our hearts in Christian love;

The fellowship of kindred minds

Is like to that above.

Before our Father’s throne

We pour our ardent prayers;

Our fears, our hopes, our aims are one

Our comforts and our cares.

We share each other’s woes,

Our mutual burdens bear;

And often for each other flows

The sympathizing tear.

When we asunder part,

It gives us inward pain;

But we shall still be joined in heart,

And hope to meet again.

This glorious hope revives

Our courage by the way;

While each in expectation lives,

And longs to see the day.

From sorrow, toil and pain,

And sin, we shall be free,

And perfect love and friendship reign

Through all eternity.

— John Fawcett, “Blest Be the Ties that Bind”

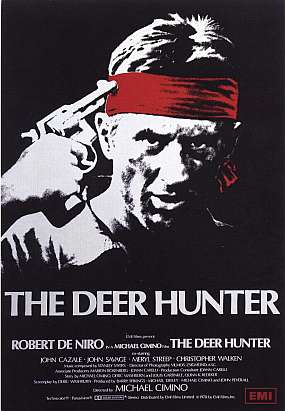

who had, by then, been reduced to a shell by his handlers and the psychological torment he’d endured.

who had, by then, been reduced to a shell by his handlers and the psychological torment he’d endured.