I have about a half dozen post ideas I’d love to toss out, but all approach epic length and I’m simply not in a “write an epic” mood today. I bet you never thought this blog was based on moods, did you?

I have about a half dozen post ideas I’d love to toss out, but all approach epic length and I’m simply not in a “write an epic” mood today. I bet you never thought this blog was based on moods, did you?

Anyway…

I haven’t written on books in a long while, so I thought I’d toss out a few thoughts on that subject, seeing that I pretend to be a novelist and all.

Lies, Damned Lies, and Publishing

I hope Benjamin Disraeli can find it in his heart to forgive the mangling I just gave his famous quote, but it fits what follows.

One of the most hackneyed pieces of advice thrown out to aspiring book writers is to forget the audience/demographic and just write your book. Nearly every seasoned writer/editor out there, when pressed for some tidbit to dispense to the yearning writing masses, will pull out this one.

Having worked in marketing at Apple—and being married to a marketing expert—I’ve always found this advice to be nonsensical. Clearly, certain subjects and characters appeal to certain market segments, so how can a novelist write without at least one finger on the pulse of the market?

But no, I’m told I’m a nut for questioning that old piece of advice.

Or am I?

Lauren Winner, writing for Publisher’s Weekly, notes an uptick in Christian Fiction featuring female pastors:

Is the Christian market ready for fictional clerical heroines?

Good question, said Andrea Christian, who acquired The Clear Light of Day by Penelope Wilcock (David C. Cook, 2007). Wilcock’s protagonist is a female minister. “I’m sure we’ll get some backlash,” said Christian. “But the writing is so strong that we took the risk.”

WaterBrook Press has published two novels featuring a female minister, RITA award-winning Heavens to Betsy (2005) and Earth to Betsy (2006), both by Beth Patillo. Patillo’s charming novels have the elements of sassy chick lit, but they’ve had to overcome a few sales hurdles. Some Christian chains, like Lifeway, balked. Ultimately, Lifeway’s top fiction-selling stores stocked the novels, but returns were heavy. That was one reason WaterBrook passed on Wilcock’s novel.

The article goes on to paint a decidedly mixed message on the success of this trend, only to end with the following:

Will the evangelical market see more fictional women clergy? Wilcock is working on two more Esme Browne novels, but Christian has not yet seen the proposals.

As for WaterBrook, they’re completely behind Beth Patillo. But her new novel—The Sweetgum Knit Lit Society, coming out in 2008—doesn’t feature any women clergy. Its characters have somewhat less controversial jobs: one’s a librarian.

Boing!

Waterbrook says they’re completely behind Patillo, but after heavy returns (and, as would follow, disappointing sales) of her last two novels, her latest one doesn’t have any content that would rile the demographic.

So yes, you can write the novel you want to write, but if the publisher’s oracle says, “The reading masses are miffed,” you may watch your contract go up in a sulfurous ball of fire.

Translation? Better write for the demographic.

So much for that old advice, huh?

And Now for the Bad News…

I noted a few days ago that I was reading Dan Allender’s Leading with a Limp. Given that books on leadership flood the secular market (and I wouldn’t give two hoots for the whole lot of them), I was glad to read a book on leadership that said that the best way to lead was to serve, be vulnerable, communicate from the heart, admit your mistakes, and cultivate an environment for others to express those ideals.

Throughout the book (which reads like a 70’s-era John Powell tome if John Powell had written a book on leadership), Allender tells stories of people who followed his leadership ideals and triumphed. Seeing that all these tales end happily bothers me. It’s not real life.

While Allender acknowledges the risk of leading in the manner depicted, where’s the chapter on what to do when that method of leading doesn’t work? In fact, where’s that chapter in most advice books? I know authors think their ideas never fail, but you and I know they do.

One of the things that bothered me about my education was when a prof tossed out a way to do X in a church, but at no point did he explain what to do when X didn’t work. Let’s face it, plenty of good ideas on how to run a church don’t wind up working for reasons that have nothing to do with the quality of the ideas. In class, I would imagine a scenario involving the wealthy church matron who funded a good percentage of the church budget. What do you do when you’ve got a transformational idea that will free your church, yet the old matron will have none of it, threatening to yank her cash if the idea gets enacted?

Folks, that’s real world and it happens all the time. Why are we so afraid to address those kinds of ideas? I’d love for authors of advice/teaching books to show us the dark side, what happens when the book’s central idea fails (or, for varying reasons, can’t be put into play at all), and what to do about it. That’s a book worth buying! Honestly, if every pastor in the country followed Allender’s ideals to the T in the next week, the week after would see half the churches in the country with a “Pastor wanted” sign out front. How does one make his book real if he provides no wisdom on what to do when the basic tenets of his book backfire?

Speaking of Books That Might Backfire…

A couple readers from my target demographic have in their hands a copy of my novel. Maybe I should include a chapter in there on what to do when it all goes wrong. Come to think of it, just about everything goes wrong in my novel—that is, until everything goes right.

So yes, I suspect I’m a hypocrite. But hey, it’s fiction, right? Slightly different rules in fiction.

At least that’s what I’ll plead in court.

%$*#!

One topic in Christian novelist circles that perpetually rises like some literary zombie is the use (or non-use) of vulgar words. As straightlaced as I am, I go against the flow and say that sometimes the material calls for profanity and all efforts to expunge it only creates surreal attempts to bypass what’s obviously being said and sometimes must be said.

However…

I read a secular book several years ago called Tell No One by Harlan Coben. I enjoyed considerably the mystery at its heart , but I didn’t read any of Coben’s other books. While in the library a few months ago, I saw another Coben book, a reprint of one of his earlier series, and picked it up on a whim. Coben received a number of writing awards for the mystery series featuring his sports agent, Myron Bolitar; the book I checked out was the first Bolitar novel.

And it was loaded with obscene language (just like pro sports is). I also picked up the last book in the Bolitar series and was surprised to see that Coben had excised all the vulgarities. Curious, I read a couple more of Coben’s other non-Bolitar books and saw a progressive dwindling of profanities, ending with none at all. The basic core of Coben’s books hadn’t changed—the same brood of amoral villains prowls the pages of the more recent books—but now Coben writes his scenes and characters free of vulgarities. How he pulled that off was so seamless that you never realized the four-letter carnival failed to roll into town.

On the other hand, most of the Christian fiction I’ve read stumbles awkwardly when it comes to dancing around bad words. Ted Dekker’s bad guy’s sanitized remarks in Thr3e bordered on cringe inducing. Worse, they undermined the entire premise of that story of Good and Evil because Evil swore like Eddie Haskell of Leave It to Beaver fame.

Maybe we should all read Coben for pointers. Sometimes even secular fiction does purity better than Christian fiction does.

And that’s it for books. Have a great weekend!

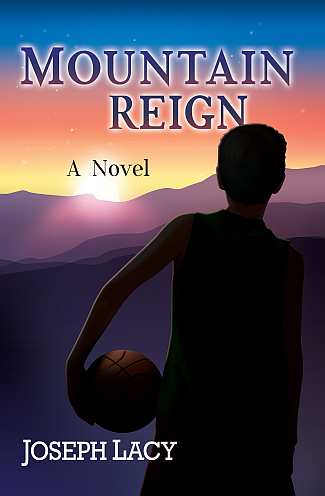

High in the hollers of ’50s-era Kentucky, God’s grace rains down on a team of boys and one determined coach in an Appalachian school destined for destruction. In Mountain Reign, author Joseph Lacy blends the best of sports fiction with a touch of the divine as he follows the hardcourt exploits of roundballers who don’t know when they’re outgunned.

High in the hollers of ’50s-era Kentucky, God’s grace rains down on a team of boys and one determined coach in an Appalachian school destined for destruction. In Mountain Reign, author Joseph Lacy blends the best of sports fiction with a touch of the divine as he follows the hardcourt exploits of roundballers who don’t know when they’re outgunned.

I had H1N1 a couple weeks ago, and it seemed to me the best thing to do while hacking up a lung was to read something escapist. You’re less likely to notice the sickness when you’re lost in another world.

I had H1N1 a couple weeks ago, and it seemed to me the best thing to do while hacking up a lung was to read something escapist. You’re less likely to notice the sickness when you’re lost in another world.