I finally got back to the second part of this short series (Part 1 here) on the Church as family. The irony is that some of the delay was due to family issues, both biological and Church.

And that’s a good segue into what I want to write about today.

What else derails the tidiness of life like family? Should I view my Facebook wall, there’s a good chance that someone’s talking about plans that went awry because of family issues. In contrast, I’ll see just as many people talking about the blessings they enjoy with their families.

You can’t have one without the other, though.

To a lot of Christians, the mark of a good church is that it doesn’t add any discomfort to their lives. In fact, I believe the number one reason that people choose one church over another relates to comfort.  (What I don’t ever hear is “The Holy Spirit told us we need to join this church.” If you’ve ever heard someone say that, please let me know. )

(What I don’t ever hear is “The Holy Spirit told us we need to join this church.” If you’ve ever heard someone say that, please let me know. )

What if we chose our biological families based solely on how little they irritate us?

We’d all be orphans.

About a year ago, I wrote on the growing issue of Christians dropping out of church life to go at the Faith as Lone Rangers. That mindset comes, in large part, from an inability to deal with the messiness that accompanies church life.

We lose something when we bolt from the messiness, though. We miss out on the character-building actions that accompany church family problems.

Those of us who have dealt with a dying parent, wayward child, addicted uncle, or perpetually needy cousin will tell you that being forced to walk through that family member’s pain, stupidity, fear, sinfulness, or need forged us stronger. If it didn’t drive us closer to Christ or show us something about our own pain, stupidity, fear, and sinfulness, I’d be shocked.

I think Rick Ianniello read my post last week, because he had a stunning quote on his blog, one I hope will make us all think:

“The central reality of church is a group of people called to an ever-deepening personal belonging of friendship with Jesus of Nazareth. The command is to abide, to dwell in him as he dwelt in the Father. You have an image that Jesus used of total intimacy. But Jesus doesn’t give us a deeper relationship with him apart from his Body. Jesus does not come alone. He can’t because Jesus already has a people, he has a family. And when Jesus comes to us he always bring his family with him. Then we say, ‘No, I want just you. What I’ve heard about you is fairly good but what I’ve heard about your family is not so good.’ And Jesus says, ‘We come together.'”— Gordon Cosby

I’m an unabashed Protestant with a leery eye for Roman Catholicism, but the one thing the Catholics do well is reinforce the idea that there’s no life outside the Church. The Cosby quote adds to this by making it clear that if you want Jesus, then you just may get the crazy aunt in the attic along with Him. If she’s a believer, that is. And she probably is. (If you’ve been a Christian long enough, you know what I mean.)

Do we think of the Body of Christ as baggage? We may say we don’t, but our actions speak otherwise:

Some lose themselves in a megachurch because they like the anonymity of the masses.

Some show up on Sunday and go invisible the rest of the week.

Some think nothing of dumping a couple grand into the church building fund, yet they can’t loosen the vise on their wallets to help a single mom pay for her son to go to church camp.

Some worry so much about their careers that they can’t take a moment away from climbing the corporate ladder to show up at an elderly church member’s house to see how she’s doing.

Some never once had the thought to sit down and hand-write a letter of gratefulness to the people who helped them become a Christian.

Some praise God with their lips on Sunday morning only to gripe about brother so-and-so on the car ride home an hour later.

Some jump from one church to another and consider themselves wise for doing so.

That last one is more like the life cycle of a common parasite, not a human being, yet this is how some people act with regards to church family.

That said, there is no difference between where the parasite and the genuine member of Christ dwell. If both are true to their natures, they should be right there in the blood and guts of the body, down amid the bile and urine, doing what they do best. Yet one sucks away life and the other gives it.

This Body of Christ, this family of God, is messy. Yet who among us would stand at the cross of Jesus and see only the mess of it and none of the glory?

Other posts in this series:

What Being a Church Family Means, Part 1

What Being a Church Family Means, Part 3

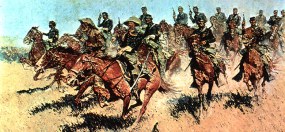

The trumpet cry as the rescuers spurred on their chargers. The enemy routed.

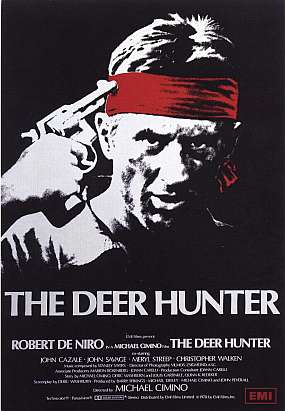

The trumpet cry as the rescuers spurred on their chargers. The enemy routed. who had, by then, been reduced to a shell by his handlers and the psychological torment he’d endured.

who had, by then, been reduced to a shell by his handlers and the psychological torment he’d endured.